By NICK CHILES

When our 10-year-old tumbled off the schoolbus today, the relief on her face tucked all up in that broad smile, it signaled the end of the five-day torture chamber that is our state’s annual standardized test.

Her feet hadn’t even touched the ground good before she and her friends were plotting a big, post-test celebration—maybe at somebody’s home, maybe in the park. But on one thing they were clear: fun would be had by all. Lots of fun. After all, the test was over and all that stretched before them, schoolwise, was three or so weeks of …well, actually it’s not really clear what their teachers will be doing over the next three weeks since the test is done.

The Georgia version of the state test is extremely high stakes: passage is required for promotion. And the stress is ridiculously high for everyone involved—students, parents, teachers, administrators. Like so many things in the world of education, what started with the best of intentions—pulling everyone up to the same high standard—has been distorted and exploited to such an extreme that the tests now represent all the things wrong with public education and very little that’s right. The high stakes were quite clear here in Atlanta, where administrators and teachers (and perhaps even the school superintendent) were driven by fear and paranoia to engage in what has been described as the largest test cheating scandal in U.S. history, getting together to do wholesale erasures of student tests, resulting last month in the indictments of 35 educators, including Superintendent Beverly Hall.

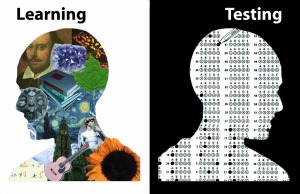

But it’s not even necessary to reach all the way to the extreme of cheating and indictments to find the poison that these tests do to the process of educating children. From top to bottom, from the worst schools to the top-ranked, the tests can snatch the minds of very good educators and turn them into a nine-month test preparation service, like a Princeton Review for little kids. Instead of capturing these young minds and fostering a love of learning and a passion for school, the educators are forced to spend far too much time drilling, prepping, reviewing for the tests. I can tell you from experience, from watching the impact this approach has on my little one, that the joy for learning little kids naturally bring to school takes a big hit.

Even top students, who should have no worries about conquering a statewide standardized test, wind up losing sleep over this ridiculous thing, their eyes wide with fear and worry. My children have all handled the tests with ease, but that hasn’t lessened their stress. And it’s not like the system then uses the test as a way to figure out how to perhaps alter the curriculum next year to bolster kids in the areas where they’re weak. Nah, none of that happens. Instead, after a summer of backsliding, they just step into another teacher’s classroom the following schoolyear and start the same mind-numbing process all over again.

For my 10-year-old, it started with Reading and ended with Social Studies, with Math, Science and Language Arts in the middle. Lots and lots of number 2 pencils and ovals and test booklets—so many in a row that there has to be some test fatigue by the time they fill in the last ovals. Since the system has understandably gotten a bit paranoid about the altering of answer sheets, my little one reported that there such a sense of heightened security that there were practically armed guards on hand to escort each test booklet once the kid handed it over.

There has to be a better way to conduct public education, a way to redesign the system so that it rewards the teachers and schools that actually engender a love of learning.

In the meantime, our 10-year-old didn’t make her way back into the house until nearly 9 p.m., full of Mexican food and stories about fun in the park. It was a joy to see her back to her pre-test self, the stress having dropped away. I’m sure it was a scene repeated all over the state and across America as our nation’s young people emerged from their state-sponsored torture chambers.

There has to be a better way.

RELATED POSTS:

1. Atlanta Cheating Scandal: A Question of Character

2. Evidence of Test Cheating Found in 200 School Districts Across the Country—A National Disgrace

3. The Most Important Advocate: What Parents Should Take Away From the Atlanta Test Cheating Scandal

Nick Chiles

Nick Chiles is a Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist and a New York Times bestselling author of 12 books, including the upcoming "The Rejected Stone: Al Sharpton and the Path To American Leadership," which he co-authored with Al Sharpton.

- Web |

- More Posts

Did you see this brilliant young man’s poem about test taking?

http://youtu.be/D-eVF_G_p-Y

What is your proposed solution? No one wants students gripped with fear, but there must be a way to evaluate what students have learned. All of life is a test.

I think the solution is to better equip and trust teachers (in teams) to evaluate students alongside their parents. This way we can focus on children as individuals. Hopefully, a team of adults who consider all aspects of a child and listen to the child self-evaluate can come up with an assessment. This is how we do it homeschooling. When I ask my kids what they are loving and doing well at and what they are struggling through, they always answer as I would answer. They see themselves honestly when given the chance and when they know that there will not be any judgement regarding their strengths, passions, and weaknesses. Nor will there be comparison to anyone but themselves.

I have blogged about this before in the past. I don’t have a problem with the testing but it shouldn’t determine whether you are promoted or not. Your grades per semester should determine that. It’s a huge problem with parents in Mass. If you don’t pass MCAS, you don’t graduate. So suppose a child is passing all year and they flunk this test they don’t graduate. There’s definitely got to be another way.

PaulaF, individual evaluations are also what is used at the excellent private school where my older daughter went through junior high, and where the 10-year-old is going next year. Instead of grades, twice a semester each teacher produces an evaluation of the child that can go on for pages. It is extremely detailed and you come away knowing exactly what your child’s strengths and weaknesses are. But of course that won’t work in a large public system where everybody needs accountability and the real estate brokers need to be able to rank the schools so they can rank the houses. When I think back to the urban elementary school I attended in the 1970s in the Northeast, we took standardized tests, but they were actually used to assess our strengths and weaknesses. And the scores were not made public and our school was not compared to the school down the street. My parents were convinced that the school was stellar and since no scores were made public, there was no way for anybody to tell them they were wrong. I can’t help but to think that if our test scores were compared to the school down the street or across town, my school—filled primarily with working class black and Puerto Rican kids—would probably eventually take on the reputation as a “bad” school because the scores weren’t as high as at wealthier white schools. And once it became described as bad, the perception of the kids, the parents and the neighborhood would suffer dramatically and start a vicious downward spiral, eventually even affecting what we kids felt about ourselves and our intelligence.